Edited By John Kuroski

Maps weren’t always sourced from the likes of Google or Apple. In

fact, maps weren’t even always printed on paper. Whether etched into

brass, carved into tomb ceilings, or drawn onto deerskins, ancient maps

show us not merely how different our ancestors’ technology and knowledge

were, but how differently they saw the world.

Sure, the ancients knew little or nothing of the New World and thought there was a massive southern continent there to balance out the lands of the north. And sure, even if the ancients were aware of the whole globe, they didn’t have the tools to accurately survey it. But the differences between modern maps and ancient maps are far deeper than that.

Today, maps are, for the most part, strictly representational: they depict the earth as it is in factually accurate geopolitical terms. But as recently as a few hundred years ago, maps were often more loosely expressive, informed to a greater extent by spirituality and art than by science.

With these 25 ancient maps, look back on a time when many may have thought the world was flat, but the maps, in every sense of the word, were not.

This

eight-rayed star fresco from Teleilat, Ghassul, dates to the middle of

the fourth millennium B.C. and might be the oldest cosmological map in

existence. According to a leading theory, the inner circle is the known

world, surrounded by an ocean, a second world, another ocean, with the

eight points representing celestial islands.

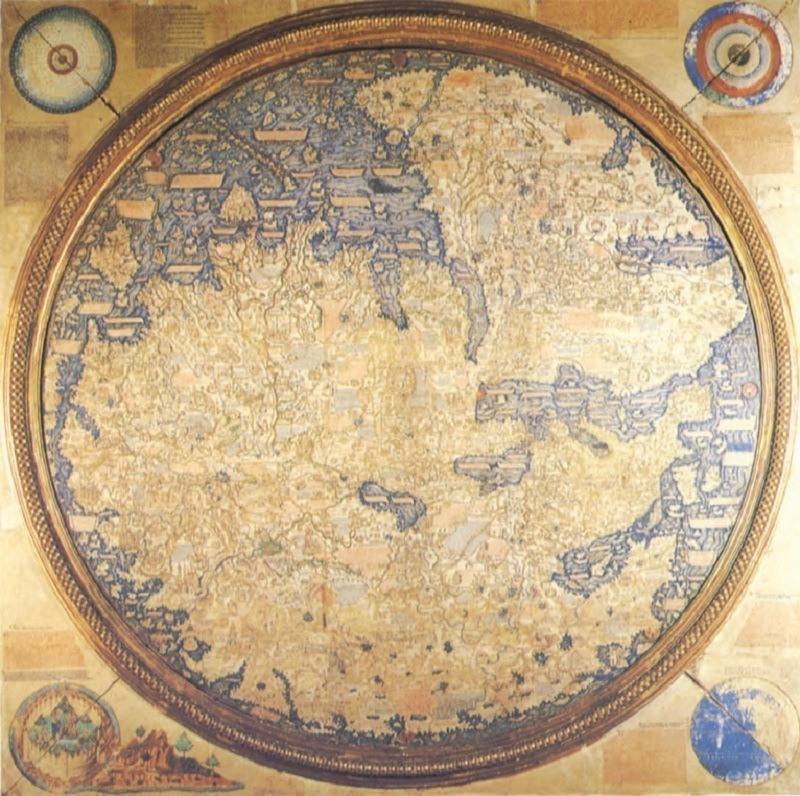

The

Fra Mauro map, named after its creator, is often considered the height

of medieval cartography. Created in 1459, the map marks the end of

cartography based on religion or tradition, instead embracing reason and

fact, including input from the likes of Marco Polo and the Portuguese

explorers in Africa.

This

1400s map of Inclesmoor, Yorkshire, holds a surprising backstory: it

was created to settle a dispute between Saint Mary's Abbey and the Duchy

of Lancaster over nothing other than the “rights to pasture and peat”

in the area.

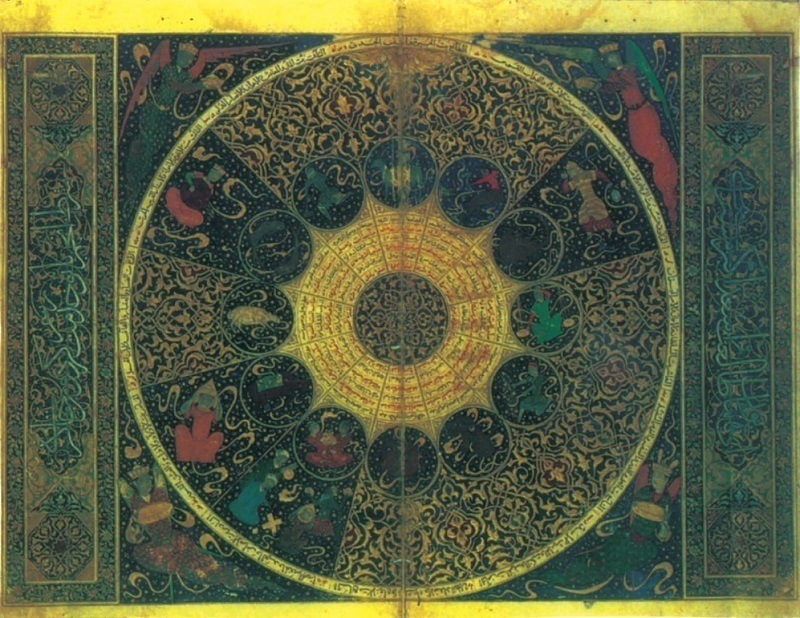

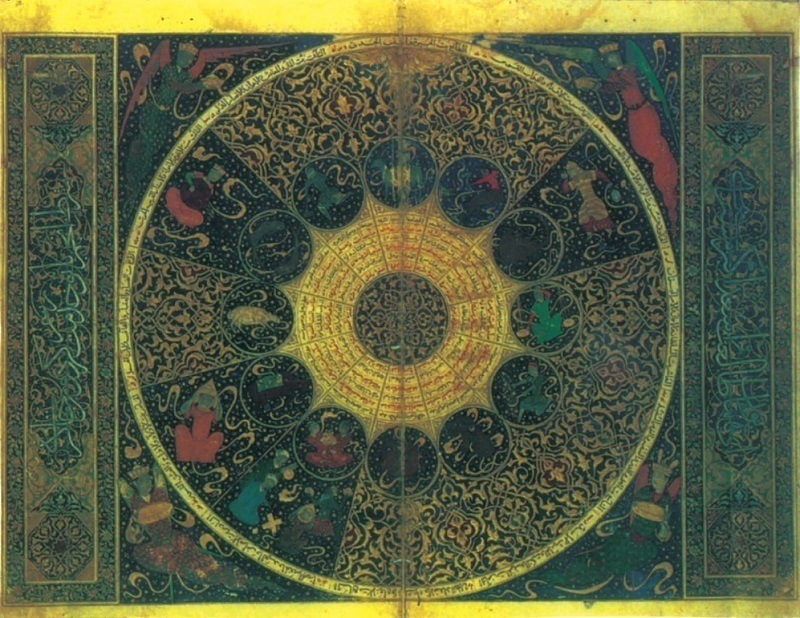

You’re

looking at an astrological map of the heavens on the night of April 25,

1384, the birthdate of Timurid Prince Iskandar. This horoscope, created

in 1411, serves as an extraordinary example of the Timurid Dynasty’s

advanced publishing capabilities.

This

planispheric map charting northern constellations and the metaphorical

figures assigned to them comes from Indian astronomer Durgashankara

Pathaka, who wrote it at an unknown point prior to 1839.

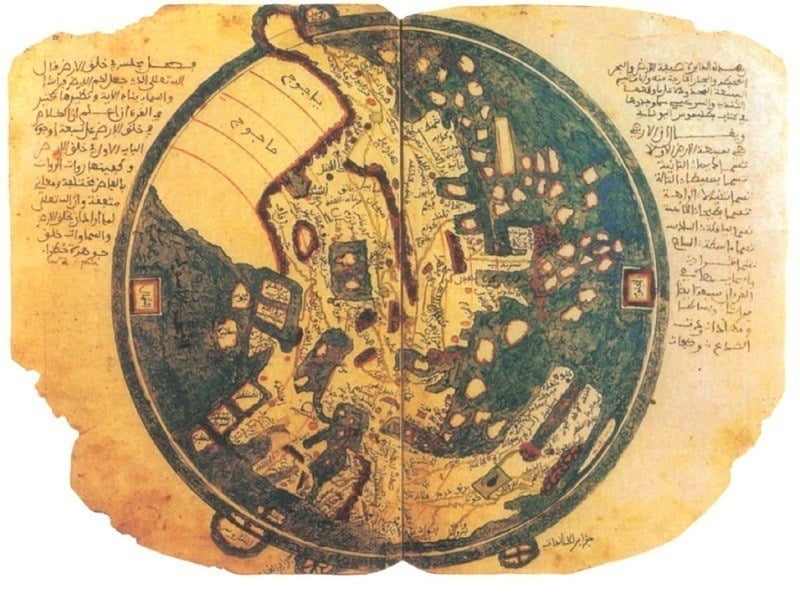

This

ancient map might throw modern readers for a loop: It puts the East at

the top of the map, reminding everyone that direction is relative. For

the Islamic geographer behind this 13th century map, Ibn Sa'id, it was a

natural choice to feature his home country front and center.

Soltaniyeh,

the ancient capital of the Mongol Ilkhanid Dynasty, is now noted as an

UNESCO World Heritage Site for its stellar, still-standing examples of

Persian and Islamic architecture. The map above, created in the 1400s,

depicts the ruins of the city walls alongside a beautiful new city,

along with plants and wildlife.

From

the History of Cartography itself: “This cornerpiece from one of two

atlases by Pietro Vesconte dated 1318 shows a mapmaker working on a

chart. The legend above the vignette reads, ‘Petrus Vesconte of Genoa

made this map in Venice, A.D. 1318,’ and it is tempting to suppose that

the portrait is of Vesconte himself.”

This

1571 globe from western India doubles as an engraved brass container

that nevertheless features the entire northern and southern hemispheres

as accurately any other maps from that era.

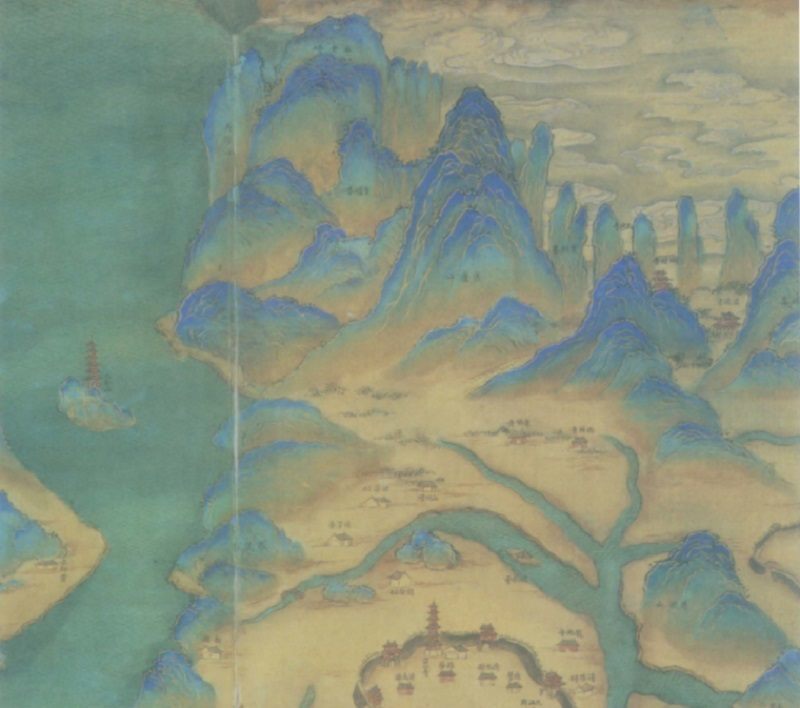

This detail from a 1700s map of China’s Jiangxi Province shows off stunningly blue mountain peaks.

Created in China in the 1790s, this map captures the entire Eastern hemisphere.

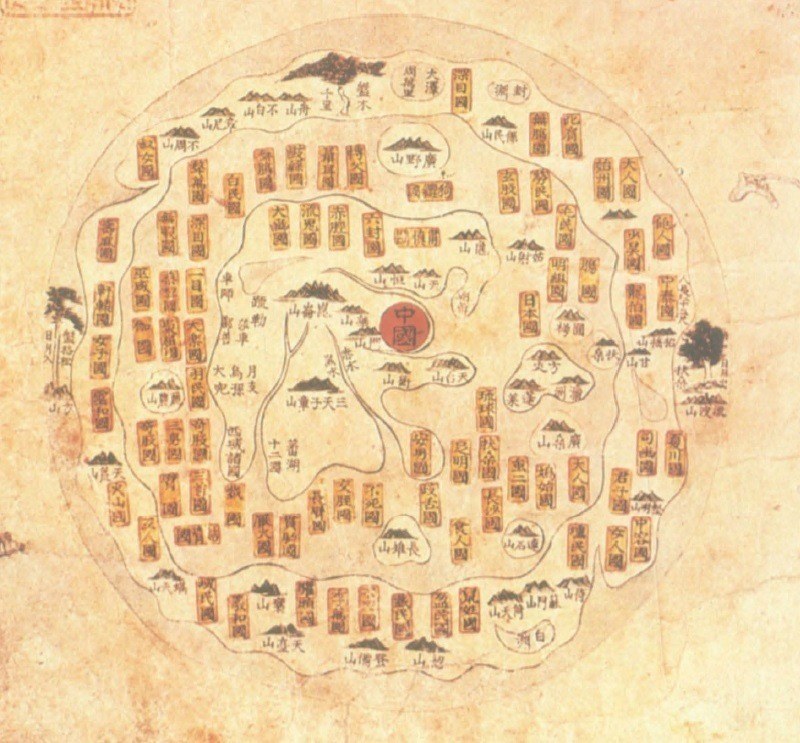

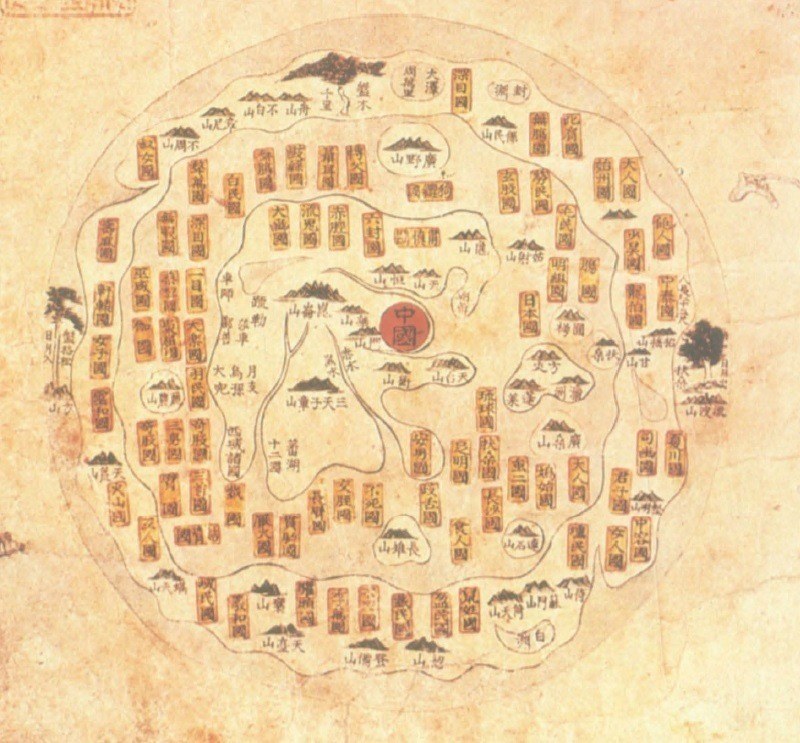

This

mid-1700s Chinese map of the world features an inner continent

surrounded by a sea holding fantasy lands and mountains, themselves

surrounded by a fictional outer ring of land. The trees to the far east

and west mark the areas from which the sun and moon were assumed to rise

and set. Data on the mythical lands was drawn from the Shanhai jing, a

collection of Chinese myths and fables dating back to the 4th century

B.C.

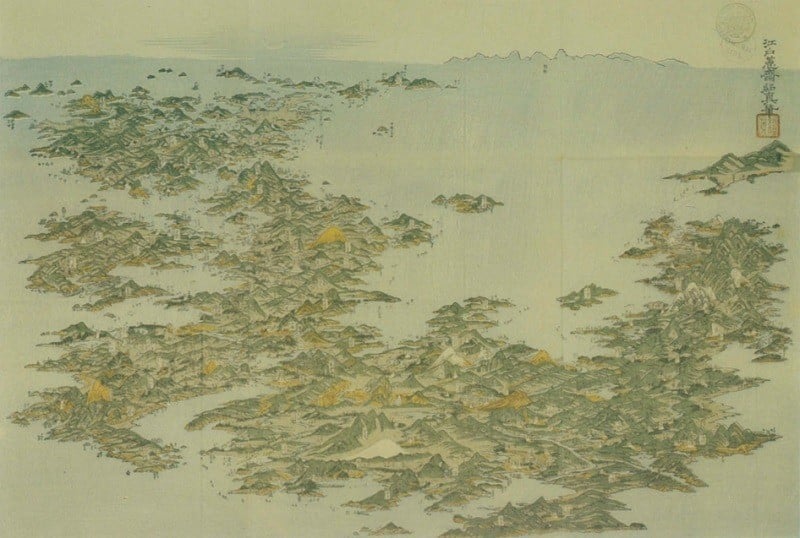

Artist Kuwagata Keisai was the first to paint an aerial view of Japan, as seen in this 1804 map.

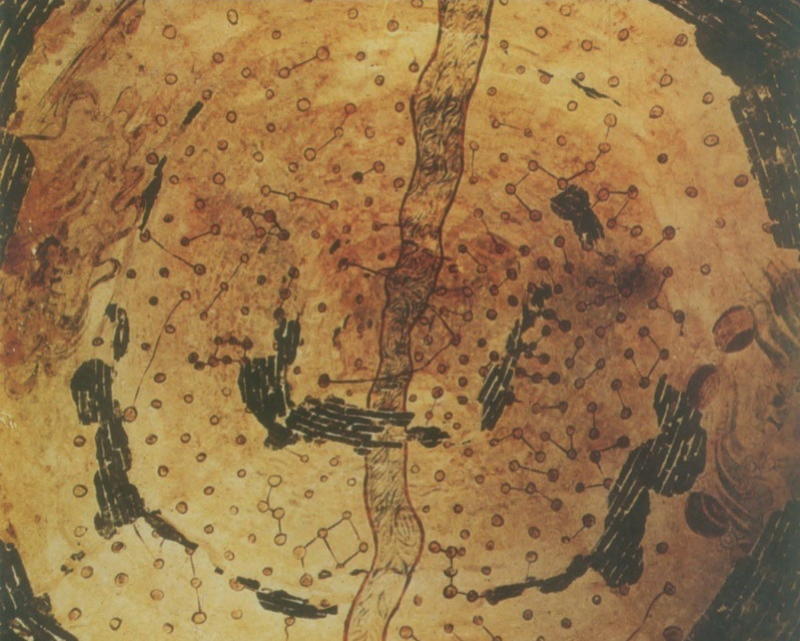

This

ancient map charting constellations amid the Milky Way is notable for

its medium: It forms the ceiling of a Chinese tomb from the 4-6th

century Northern Wei dynasty. It’s also the earliest surviving portrayal

of the entire breadth of the visible sky.

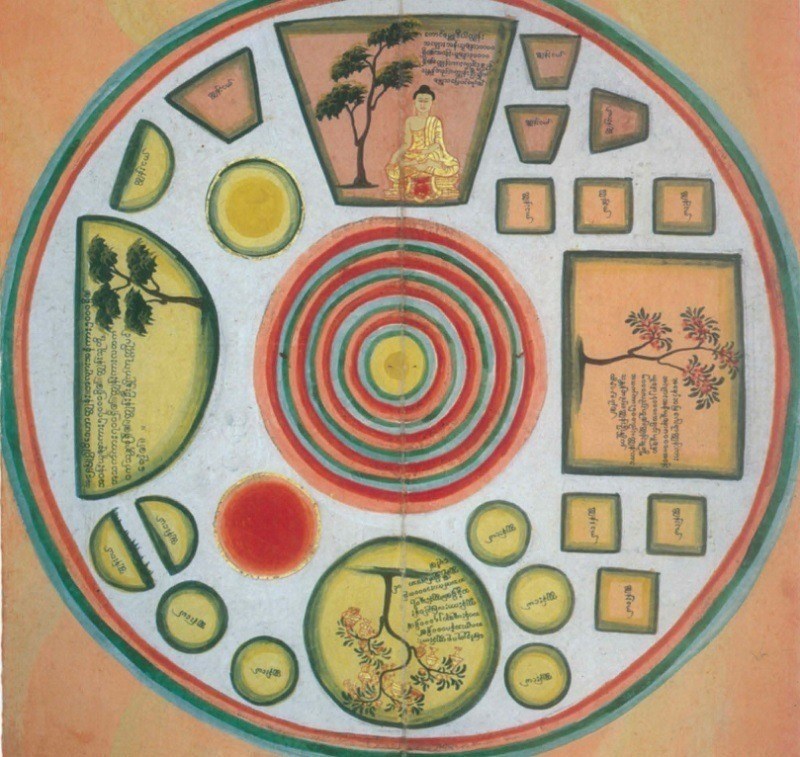

This

late-1800s Burmese painting depicts the entire universe. The large

shapes are continents, the smaller ones are sub-continents, and the

whole scene is capped with a rainbow-colored rim surrounding the

universe itself. Like all cosmological maps, this one relies on heavy

speculation that blurs the line between science and myth.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

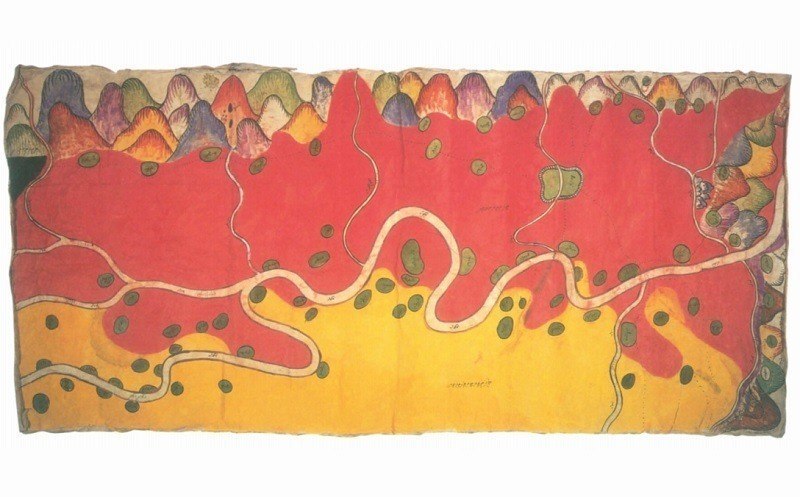

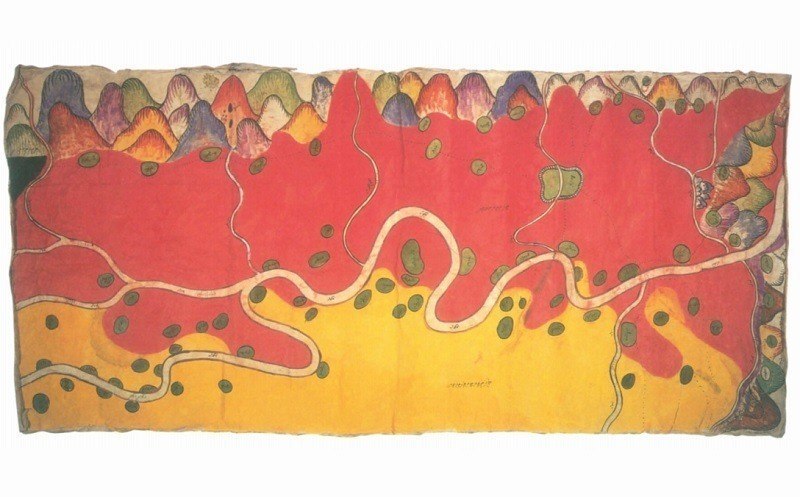

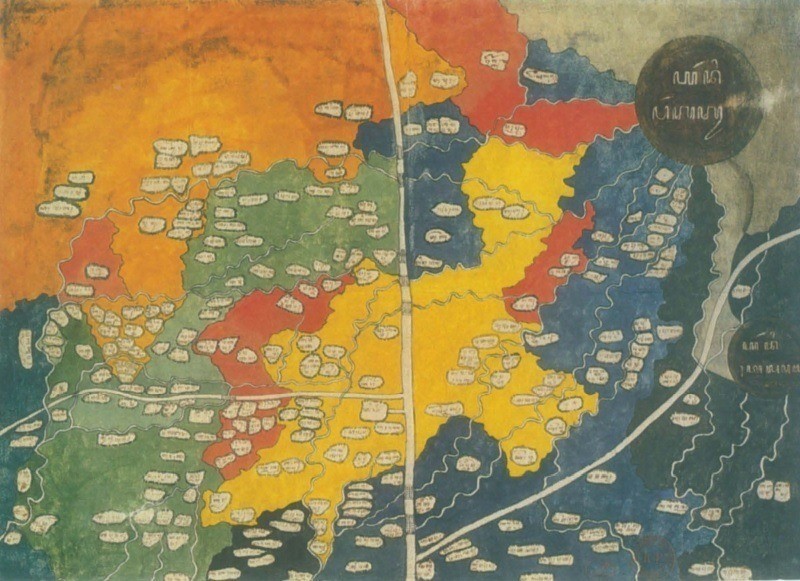

This

1889 map of the Nam Mao River covers a border dispute between China (in

bright tempura red) and Burma (in yellow). According to The History of

Cartography, the details are “remarkably accurate.”

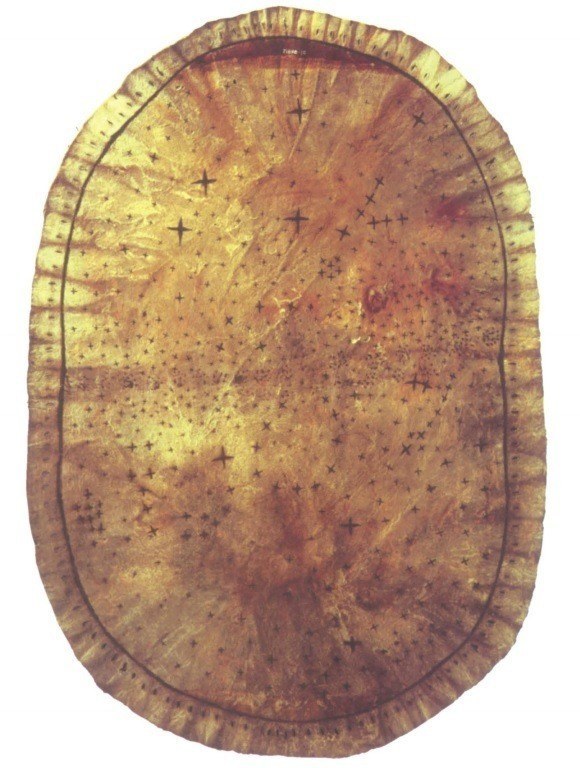

Skiri

Native Americans created this star chart on a tanned antelope hide or

deerskin, found Pawnee, Oklahoma, in 1906. That row of small dots across

the middle represents the Milky Way, which was thought to be a path

used by departing spirits.

This

diagram maps fertility on a cosmic scale, as depicted by a member of

the Tucano people, a group indigenous to South America. The coded map is

designed to highlight the natural order of the world, as understood by

the Tucano.

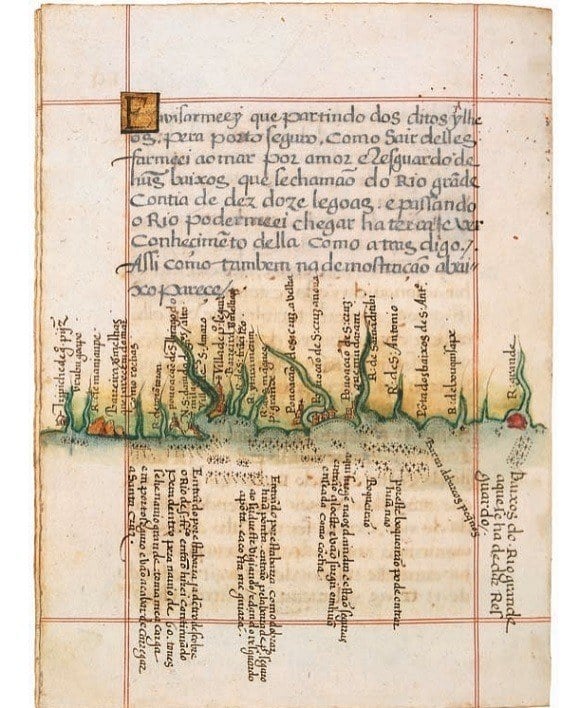

The

Brazilian coastline is mapped out on this page, which also provides

handy guidelines on how to enter and leave sea ports. It’s from a

Portuguese roteiro, or nautical guide, and depicts the coast near Porto

Seguro, where explorer Pedro Álvares Cabral first reached South America

in 1500.

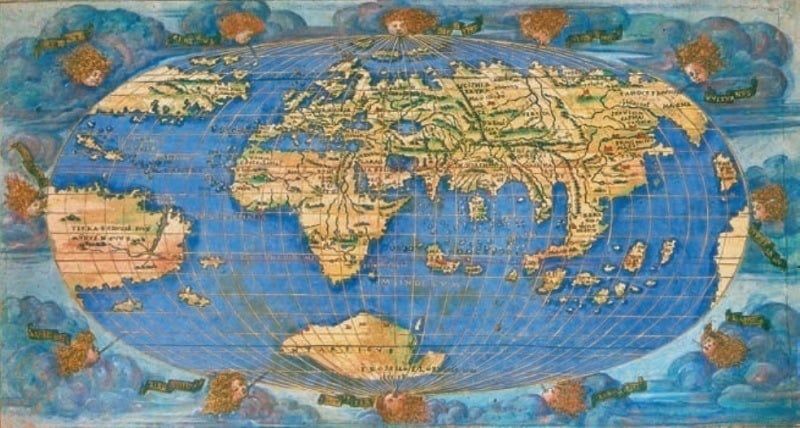

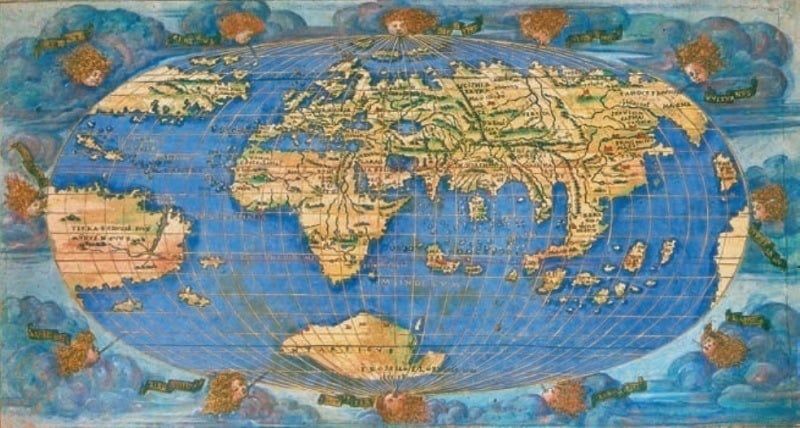

One

of just two known colored editions, this 1508 copy of Francesco

Rosselli’s Oval World Map was one of the first to incorporate the

Americas following Christopher Columbus' voyages.

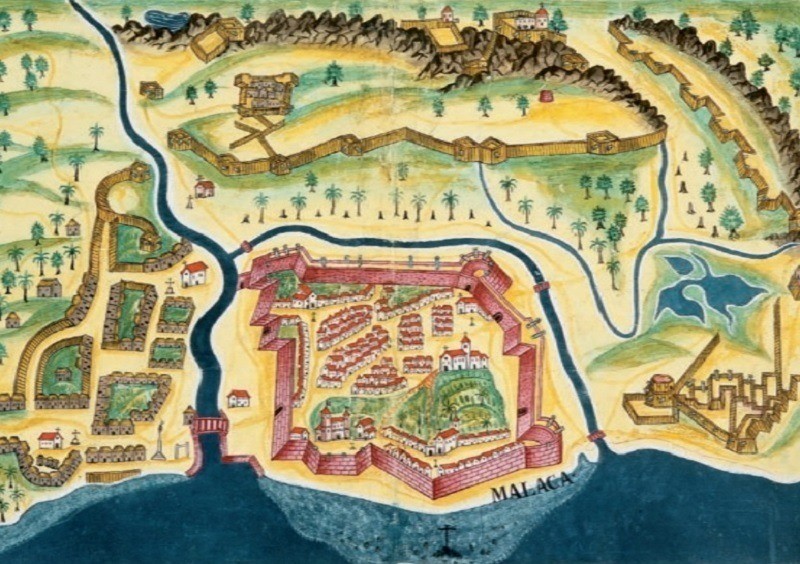

This

scene of the Fortress of Malacca comes from António Bocarro’s 1635 O

Livro Das Plantas, a military map book for Portuguese India.

This

aerial 1537 map of the city of Rothenburg ob der Tauber (in modern-day

Germany) adds elements of landscape painting to the usual cartography.

This

heart-shaped Earth in this 1536 watercolor-and-wood-engraving by French

cartographer Oronce Fine isn’t entirely accurate: He included a massive

southern continent, Terra Australis, which was hypothesized to

counterbalance the northern continents.

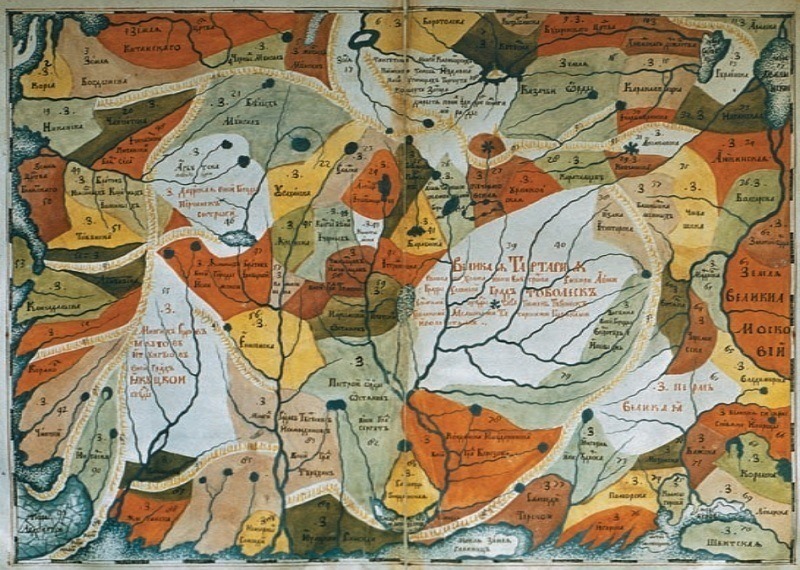

The early-1700s ethnographic map of Siberia shown here charts the region’s archaic tribal boundaries in a colorful patchwork.

This

mid-1800s map of central Java, Indonesia is presumed to be of Dutch

origin, designed to track revenue and labor. The two dark circles to the

right denote volcanoes.

All maps sourced from The University of Chicago's History of Cartography.

沒有留言:

張貼留言